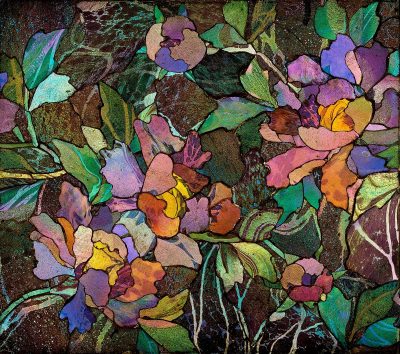

One of the most exciting discoveries to be featured in the exhibition, Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics, is that Louis C. Tiffany’s glassblowers were instrumental in making a significant portion of the flat glass used to create the firm’s celebrated mosaics. Intriguing types of decoration typically seen in Tiffany’s blown glass vases were also artfully incorporated into mosaic compositions, such a lustrous rainbow iridescence, threaded patterns, or bubbly pitted surfaces.

- Mosaic panel with peonies, about 1900–1910. Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company or Tiffany Studios. Glass mosaic, bronze. H. 34.5 cm; W. 39 cm; D. 2 cm. The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York (77.4.91). Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York

- Vase, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, about 1895–1896, Glass. On loan from The Rockwell Museum, Corning, New York, 82.4.144.

Tiffany’s mosaics most commonly incorporated flat glass made by rolling a molten gob of glass into sheets that could then be cut into smaller pieces for intricate mosaic compositions. This is a fast and efficient way of producing sheet glass, and also used to create glass selected and cut for Tiffany’s windows and lampshades. However, it isn’t possible to achieve through this rolled technique the iridescent and complexly patterned surfaces in some of the flat glass we encounter in Tiffany’s mosaics.

The Neustadt’s glass archive provided us with important clues about the glassmaking processes used to make mosaics. We discovered pieces of glass that looked as if they had been made by employing a technique called cylinder glassmaking. It is a process typically associated with historical window glass production, but Tiffany’s glassblowers used it in a new way to create an amazing variety of patterns and surface finishes, which greatly expanded the glass palette previously available to mosaicists.

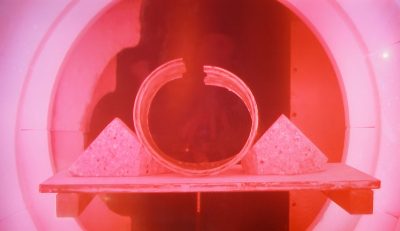

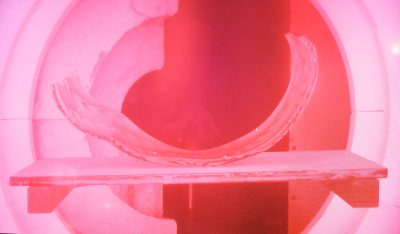

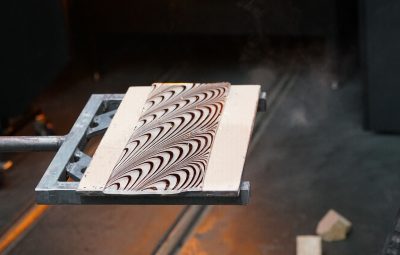

In the cylinder method, glass is transformed into a thin sheet through the process of glassblowing. Glassmakers begin the process by gathering glass of one color and applying decoration such as threaded patterns in contrasting colors, embedding murrine (see below), or exposing the hot glass to metallic oxides to create an iridescent surface. The glass is then inflated and shaped into an elongated cylinder form. The cylinder is shaped and opened on both ends to create a tube. Finally, the cylinder is split along its length and placed in a chamber heated to 1,500 degrees. At this temperature, the softened glass can be coaxed open into a flat sheet for mosaic selectors and cutters to use.

- Gaffer Chris Rochelle opens one end of a bubble to form an open cylinder.

- The split cylinder begins to soften in the heated chamber.

- The cylinder gradually unfurls to form a sheet.

- The flattened cylinder

Piece of flat glass made using cylinder technique; Tiffany

Furnaces, Corona, New York. The Neustadt Collection of

Tiffany Glass, Queens, New York

We were able to determine the approximate dimensions of Tiffany’s cylinders by looking at nearly complete examples discovered in The Neustadt’s glass archive, and through experimental work in CMoG’s Amphitheater Hot Shop, we reproduce the effect for videos on display next to Tiffany’s glass from The Neustadt in the exhibition. You can also stop by CMoG’s Amphitheater Hot Shop to watch the process in our daily Tiffany’s Palette demonstration.

“Morning Glory Paperweight” Vase

Tiffany Studios, about 1914

Glass

CMG 97.4.125, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Howard Stein

An especially unique use of cylinder glass (and one that really excited us to discover) was the inclusion of murrine to create the detailed representations of flowers in The Dream Garden. This decorative method was already used at Tiffany’s furnaces to create flowers, such as morning glories, for glass vases.

To create murrine, colored glass patterns are stretched into long canes, and sliced into disks to reveal the pattern in cross section. Murrine were imbedded in the surface of the molten glass gob and then, using the cylinder glass process described above, transformed into flat glass. By doing this, the murrine were stretched and thinned, creating a painterly look used so effectively in this tour de force mosaic. The level of detail seen in this single small flower attests to the skill and dedication of Tiffany’s team to achieve unprecedented effects in glass mosaics.

Detail of mural, The Dream Garden, 1916. Tiffany Studios. Glass mosaic. Curtis Publishing Company Building (now The Curtis Center & Dream Garden); mural in the collection of Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (2001.15, partial bequest of John W. Merriam; partial purchase with funds provided by a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts; partial gift of Bryn Mawr College, The University of the Arts, and The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Blown and cut glass murrine, Tiffany Furnaces, Corona, New York. The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, Queens, New York.

Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York

It has been thrilling to look at Tiffany’s mosaics through the lens of glassmaking, rather than simply focusing on the beauty of the finished object or panel. The clues discovered in The Neustadt’s Glass Archive and the insights shared by CMoG’s glassblowers provide a richer, fuller picture of the complicated creative process undertaken by Tiffany’s firm to make these magnificent mosaics.

This post was co-written by Eric Meek, CMoG’s manager of Hot Glass Programs, and Lindsy Parrott, director and curator of the Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass.

Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics is on view at The Corning Museum of Glass through January 7, 2018. Learn more about the exhibition.