Late in 2016, a second-grade girl named Aditi faced a common pesky challenge in an uncommon way. In a blog entry, “The Secret About Lice,” she wrote:

On December the 6th I got lice on my head. I was curious to see what it was. So me and my Dad took two lice that I had on my head and put it under the Foldscope. I learned lots of new things about lice. I learned that lice are insects because they have six legs. I saw that the antenna had five brick-like things in the adult louse and four brick-like things in the young-ling. I read they are called flagellomeres. I saw that the lice digested my blood in its gut. In the microscope I saw that there are two claws on the legs. One was big and shaped like a hook and the other one was small and shaped like a baby hook.

Aditi is a member of the DC Micronauts, a group of school-aged children who meet regularly to explore the tiny worlds around them. They use Foldscope, an origami-based, single lens paper microscope invented by Manu Prakash and James Cybulski.

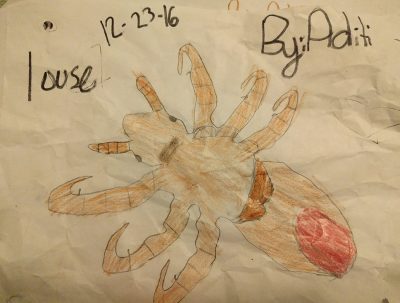

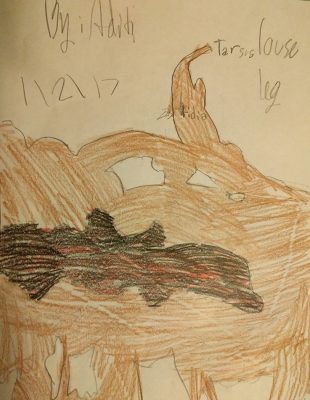

With a flashlight for additional light, Aditi was able to project and magnify her specimen’s image so that she could draw it in detail and understand lice even better.

- Aditi’s drawing of a louse based on what she saw through the Foldscope.

- Aditi’s drawing of the left side of a louse as seen through the Foldscope.

Great minds think alike, so it’s no surprise that lice have fascinated microscopists throughout history. In 1665, Robert Hooke (1635-1703) published one of the first images of a louse ever viewed under a microscope in his book, Micrographia. Hooke’s ground-breaking volume is on view at The Corning Museum of Glass as part of the exhibition Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope.

Looking closely at the tiny thing begging for her attention didn’t just put Aditi in the same company as naturalist, Robert Hooke, but also the father of microscopy, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723). In fact, a few hundred miles from Aditi at The Corning Museum of Glass, one of the last surviving examples of van Leeuwenhoek’s extraordinary hand-crafted single lens microscopes from the 1600s sits in an exhibit case across from a Foldscope, the same type of single lens microscope that Aditi uses today to make her discoveries.

Aditi had never heard of van Leeuwenhoek when she wrote her blog post, but their journeys are similar.

Simple microscope, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek,

Delft, the Netherlands, c. 1675 – 1723.

Lent by Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Image Courtesy of Museum Boerhaave.

Van Leeuwenhoek didn’t start his work with microscopes as a scientist but as a textile merchant. Looking through one of the tiny glass beads that served as a lens allowed him to inspect the cloth he sold. Like Aditi, once he understood the power of the tool in his hands he used it to explore the world around him. Van Leeuwenhoek was curious about lice he found on his body, too, and used his microscope to examine it.

Van Leeuwenhoek recorded his discoveries and shared them with other scholars and naturalists, most notably members of The Royal Society of London. Aditi also shared her discoveries, but she has advantages that van Leeuwenhoek didn’t. In the era of smartphones, the Internet, and frugal science tools such as Foldscope, which costs about a dollar for materials, even young people like the DC Micronauts can be part of a scientific community.

And their help is welcomed. The microscopic world is so vast that professional scientists know they could never explore it thoroughly alone. Aditi and her colleagues are part of a citizen science movement. For example, Aditi’s father, Laks, a professional microbiologist, has started a pollen database that is fed by observations gathered by citizen scientists with Foldscopes from around the world, including his daughter. He said, “You have to teach people to be organized in how they present their data, but the contributors can fill in the gaps if they capture the pollen size and shape of a missing flower, or a petal structure, and so on. I don’t always know who is giving the information. It could be a chemist, a physicist, a writer, an artist, or a 7-year-old kid.”

Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope is open 9 am – 5 pm every day through March 19, 2017. This exhibition tells the stories of scientists’ and artists’ exploration of the microscopic world between the 1600s and the late 1800s. Unleash your sense of discovery as you explore the invisible through historic microscopes, rare books, and period illustrations, and take a #cellfie in the Be Microscopic interactive.

1 comment » Write a comment