Marvin Bolt, the Museum’s curator of science and technology, traveled to Europe last fall to research some of the world’s oldest telescopes. Read along to hear about his adventures and discoveries.

Jena, Germany, has a strong optical glass tradition that goes back to the 1840s. Carl Zeiss, later joined by Ernst Abbe and finally by Otto Schott, invented the concept of specialty glass. By methodically changing glass recipes to create many kinds of optical glass – used in cameras, medical devices, and planetarium systems, for example – they began to develop glasses with a variety of very specific properties. The Zeiss firm logo is based on the two kinds of glass – crown glass and flint glass – used to make an achromatic microscope, the motivation for the three innovators to join forces in 1884.

Jena, Germany, has a strong optical glass tradition that goes back to the 1840s. Carl Zeiss, later joined by Ernst Abbe and finally by Otto Schott, invented the concept of specialty glass. By methodically changing glass recipes to create many kinds of optical glass – used in cameras, medical devices, and planetarium systems, for example – they began to develop glasses with a variety of very specific properties. The Zeiss firm logo is based on the two kinds of glass – crown glass and flint glass – used to make an achromatic microscope, the motivation for the three innovators to join forces in 1884.

This optical tradition also led to the founding of an optical museum in Jena (below left), where we spend two very productive days.

- Optical Museum Jena

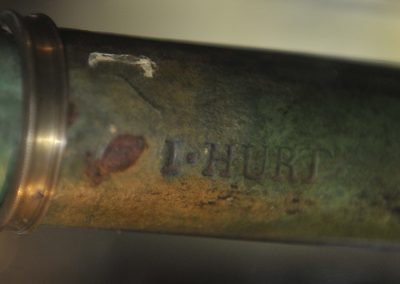

- Telescope by John Hurt

After searching for telescopes on display and in their store room, we settled down in the basement to have a look at what we had assembled. One instrument made by John Hurt caught our attention, not because of its unique features but because we had seen no other examples by this English maker (above right). We explored a few details of an 18th-century example made by Johann Rudolph, the fourth known example by him, again not because of its optical features but because he was the director of the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon in Dresden in the 18th century.

One telescope going back to 1660 took up some more time, but the undoubted treasure was an anonymous example. Its main tube features two words: “Tubus Coelestis.”

One telescope going back to 1660 took up some more time, but the undoubted treasure was an anonymous example. Its main tube features two words: “Tubus Coelestis.”

Over the years, many people have no doubt seen this, and likely assumed it was simply a telescope for doing astronomy. To our great surprise, we determined that it was an example of a style that was widely known, and fully described, but of which there are no other known examples from the 17th century. Or even through the middle of the 18th century. None. And here, in our hands, at last, was one!

Clearly, we had to spend a lot of time making sure of what we had. We documented everything we could, and then did the most fun part: we looked through it.

This took a little ingenuity, a flexible tripod, some duct tape, and an open window.

And we saw what a Keplerian should reveal, an upside image.

The image quality is consistent with a 17th-century lens.

The setup might be a bit unorthodox, but the results are solid. The academic thing to do is to write up a paper on this. So we will.

The setup might be a bit unorthodox, but the results are solid. The academic thing to do is to write up a paper on this. So we will.

After devoting the better part of the day to this unique item, we were pretty pleased. Then, as usual, reality hit. The train to Berlin was cancelled, forcing a circuitous rather than a direct route, delaying our return there until after midnight in advance of a 7 am flight to London. Even so, it was a stellar two-day visit.