Warren Bunn, collections and exhibitions manager for The Corning Museum of Glass, talks about what went into installing the Contemporary Art + Design Galleries—from the challenges of working in a new, innovative space to his favorite objects to install. Warren has worked at the Museum for 12 years, but has 20 years of experience installing art. He estimates he’s installed more than 100 shows and exhibitions.

Q: What was your role in planning this expansion?

A: I always think of myself as sort of the Lorax for the collection. I speak for the glass. There are certain things I would push for like the 10-foot door access and passage from the loading dock to the galleries. Contemporary sculpture keeps getting larger and we wanted to make this facility high-functioning for the future.

Q: How do you work with a curator, in this case Tina Oldknow, senior curator of modern and contemporary glass, to put together a new exhibit or gallery?

A: The curator chooses what we acquire for the collection and has a desire for where and how they’d like to display the art. I always joke with Tina that she may want a piece to hover in space, but I can’t defy the laws of physics. Curators many times are thinking about aesthetics, but we have to strike a balance between safety and aesthetics.

Curator Tina Oldknow and collections & exhibitions manager Warren Bunn scatter Carroña’s broken glass within the display.

Q: What are some of the unique aspects of the space when it comes to installing glass?

A: There’s no ceiling. In most museums when you need to hang something from the ceiling, you have a structure, but here we have skylights and these beautiful concrete beams. We had to come up with a strategy so that objects that need to be suspended, like It’s Raining Knives by Silvia Levenson, could sit on top of those beams and be anchored, but still visually pleasing, so your focus is on the art and not the mechanics.

It’s Raining Knives, Silvia Levenson, Vigevano, Italy, 1996, reconfigured in 2004. 19th Rakow Commission. 2004.3.29.

Q: When you could finally start working in the galleries, where did you begin?

A: We started looking at how our model and plans realistically matched up to what had been built. We thought about the flow of how we were going to install—starting with objects furthest away from our access point. Then the exhibition fabrication company came to set up the casework—decks, wall cases, and platforms—that we had been working with them to build for nearly two years. They worked ahead of us so we could install exhibits as they moved through the space putting in the exhibit furniture.

Q: What goes into installing a single piece of glass?

A: There are so many different pieces with different installation instructions in the new wing that we created a master binder. When it’s time to install a particular piece, we flip to that page, and there are pictures, as well as unpacking and installation instructions. We orchestrate the safe moving of the object, track it in our database, and determine the needs for that piece. Is it going in a wall case? On a platform? For objects like Black Cube, we can’t lift it up and over the glass barrier, so we need to tell the exhibition fabricators to leave the glass and stanchions off so we can install the artwork first and then place the enclosure around it.

Q: How do you go about moving an object?

A: Glass objects by their nature are fragile, so we need to assess the needs of each piece. They’re sort of like children. Each kid has a different way of learning and a different way they want to be talked to, so with an object you need to determine how it wants to be moved—the fragility, the safety, the weight of it. And you need to figure out how to keep the people moving it safe. Our new Roni Horn piece weighs nearly a ton, so you can’t just pick it up with your hands and move it. It’s strapped, slung in a rig, and moved with a gantry. We utilize our tools, and have a good communication system. We also involve our conservation staff. If we have something that’s fragile, we want to talk to them about all the challenges of the piece.

Untitled (“The peacock likes to sit on gates or fenceposts and allow his tail to hang down. A peacock on a fencepost is a superb sight. Six or seven peacocks on a gate is beyond description, but it is not very good for the gate. Our fenceposts tend to lean and all our gates open diagonally”), Roni Horn, 2013.

Q: How long can it take to install a single object?

A: The first time we set up Forest Glass, it took us a week. The artist, Katherine Gray, was here assembling the piece aesthetically. It has over 2,000 objects within the composition, so it’s very time and labor intensive. We knew we’d be setting up the piece again, so when we de-installed it, we took pictures of each shelf and packed all the glass on that shelf together in a crate, so it shouldn’t take quite as long to install this time.

Q: Are there any particularly challenging pieces to install?

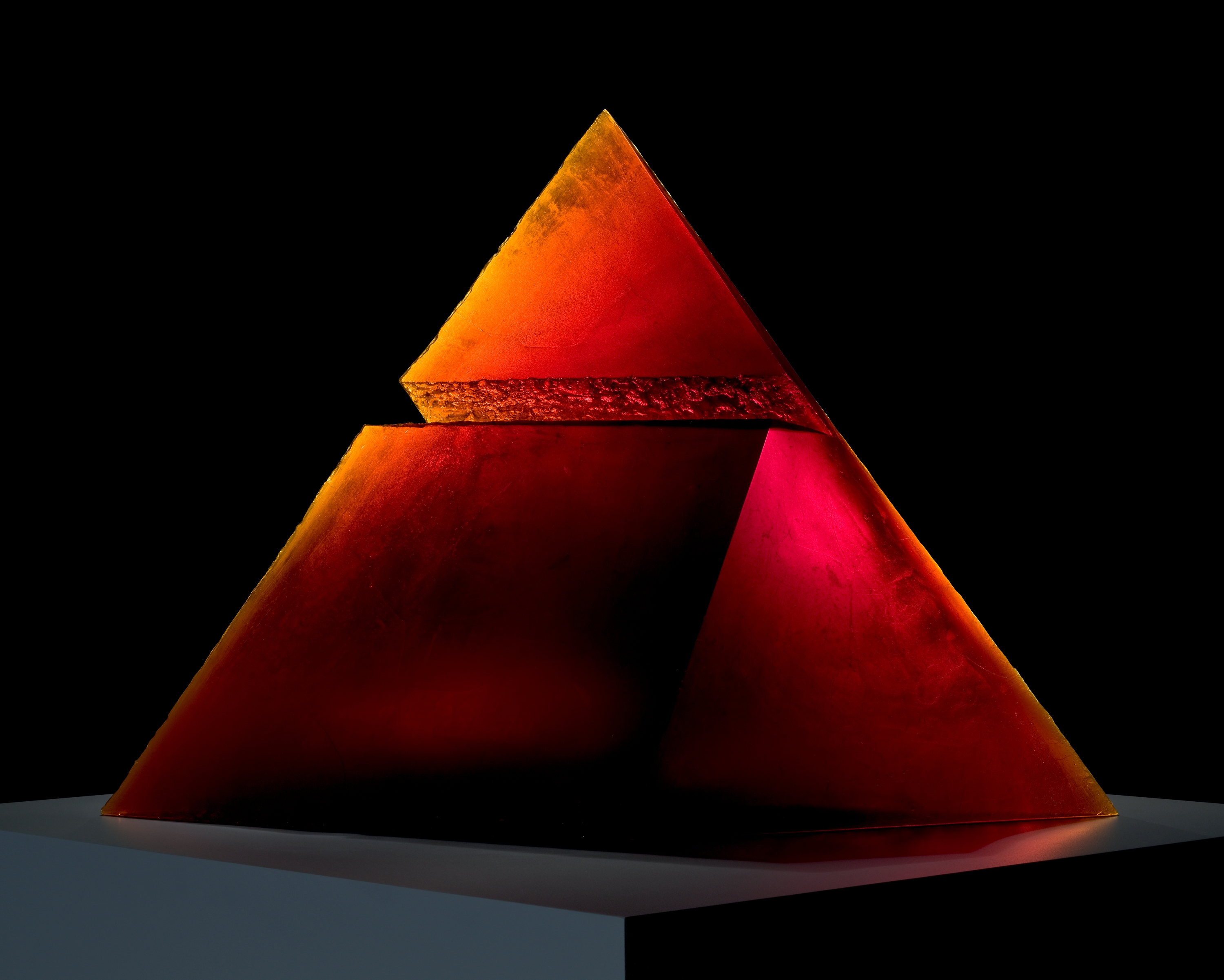

A: A lot of them! Some are challenging because they’re new and we’ve never set them up before. Evening by Cerith Wyn Evans is new and very complex because of the technical aspects of not only setting it up, but making it run reliably into the future. It blinks a poem in Morse code, but the program to make that happens only runs in Windows XP. We have to not only set up the piece, but come up with a strategy to deliver power to it, and the monitor that shows the translated poem. Other pieces are challenging just because of their sheer fragility. Red Pyramid is one of my favorite pieces in the entire museum, but few things make me as nervous to move. It’s like trying to move a car, but all of its edges are like Pringles. If you put too much weight down on one of the edges, it can damage the piece. Susan Plum’s Woven Heaven Tangled Earth feels like picking up air, and typically when we move it, you can hear it giving off some of its stress with clinks and tings. It’s sort of frightening, but we understand it’s just doing what it needs to do.

- Museum staff putting together Evening by Cerith Wyn Evans, a colorless double-tiered glass chandelier.

- Evening, Cerith Wyn Evans, London, UK, 2008-2013. 2013.2.2.

- Woven Heaven Tangled Earth, Susan Plum, Brooklyn, NY, 1999. 2001.4.70

- Red Pyramid, Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová, Zelezny Brod, Czech Republic, 1993, Gift of the artists. 94.3.101.

Q: Any objects that are personal favorites when it comes to installation?

A: We’d never installed Carroña (Carrion) by Javier Pérez before. It’s a shattered chandelier with taxidermied crows, and there are bags of broken glass you just dump out. I think this one has such a bold presence and is really going to be a visitor favorite. Endeavor, by Lino Tagliapietra, when it’s up and done right, it just hovers in space and people really love it. Karen LaMonte’s Evening Dress with Shawl is really heavy—almost a thousand pounds—but it’s such a beautiful piece when it’s lit and installed. It’s like a dream.

- Carroña (Carrion), Javier Perez, Berengo Studio, Murano, Venice, Italy, 2011. 2012.3.33.

- Endeavor, Lino Tagliapietra, Seattle, WA, 2004. Purchased in honor of James R. Houghton with funds from Corning Inc. and gifts from the Ennion Society, the Carbetz Foundation Inc., James B. Flaws and Marcia D. Weber, Maisie Houghton, Polly and John Guth, Mr. and Mrs. Carl H. Pforzheimer III, Wendell P. Weeks and Kim Frock, Alan and Nancy Cameros, the Honorable and Mrs. Amory Houghton Jr., E. Marie McKee and Robert Cole Jr., Robert and Elizabeth Turissini, Peter and Cathy Volanakis, and Lino Tagliapietra and the Heller Gallery, New York. 2005.4.170.

- Evening Dress with Shawl, Karen LaMonte, Zelezny Brod, Czech Republic, 2004, Gift in part of the Ennion Society. 2005.3.21.