Conservation occurs mostly behind the scenes, but the effects of conservation can be seen throughout our galleries. Here are 10 conservation-related stories you can see in the museum right now.

Nilotic bowl (2012.1.1)

Broken objects can often reveal details about how they were made that could not otherwise be seen. The broken fragments of this ancient Roman bowl provided useful insights into how the flameworked decorative elements, mostly birds and plants historically found in the Nile delta, were incorporated into the translucent purple background of the bowl. In the cross sections visible on the break edges, the flameworked elements have a sharpness that strongly suggests that the purple background glass was much hotter, and therefore softer, than the decorative elements when they were embedded. Learn more about this bowl, how it was made, and its treatment in an article in the Journal of Glass Studies, Vol. 57, and this 2014 blog post.

- Nilotic bowl in its case in Glass of the Romans.

- Inlaid Bowl with Nilotic Scene, Roman Empire, 300-499. Purchased in part with funds from the Ennion Society and the Houghton Endowment Fund. 2012.1.1.

- Fragment with cross section showing sharpness of flameworked decorative elements.

Plate (66.1.35)

This ancient Roman plate was one of the hundreds of objects that were restored shortly after the 1972 flood (read more about the flood in a 2013 blog post and in this article) which submerged the museum in more than 5 feet of muddy water. At the time, the Museum didn’t have a conservation department (it was created in the aftermath of the flood with the Museum’s photographer, Ray Errett, becoming the first conservator). So conservators and volunteers from all over the world came to help with the recovery of the devastating damage to the collection.

This particular object was already damaged and repaired when it come into the museum’s collection in 1966, but the water from the flood likely weakened or destroyed those repairs. It was re-treated in 1973 by Dorothea and Rolf Wihr, two expert German glass conservators. According to their treatment report, after the remaining fragments were glued back together, they reconstructed the missing parts with clay. Then they made a mold of the entire reconstructed plate with silicone rubber. The silicone mold was then used to cast an epoxy into the missing areas. The total treatment took 29 hours over 22 days.

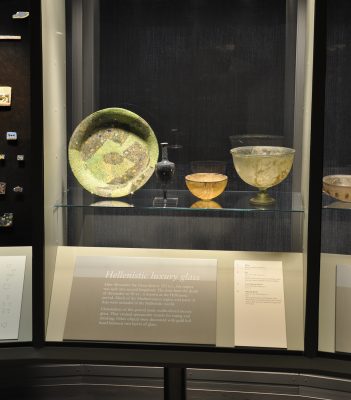

- Plate in its case in The Origins of Glassmaking Gallery.

- Plate, Egypt or Rome, 225-100 BC. 66.1.35.

- Detail of the plate. The light green sections are fills with discolored paints.

Sometime after the Wihrs completed their treatment, these fills were painted to resemble the surrounding glass. Originally, the color was likely a much better match, but over time the paint has discolored causing the fills to become much more apparent.

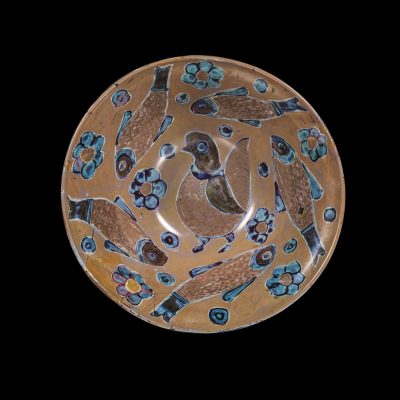

Islamic bowl with bird and fish (99.1.1)

This bowl, displayed in the primary Islamic case in the 35 Centuries of Glass Galleries, had old repairs that failed and was completely retreated a few years ago. Read about the process in this previously published blog post.

- The Islamic bowl in its case in Glass in the Islamic World.

- Bowl, probably Egypt, 900-1099. Gift of Lyuba and Ernesto Wolf. 99.1.1.

- The bowl during conservation.

Pitcher with Animals and Birds (59.1.489)

If you look carefully at this relief-cut pitcher, you might notice that is has a colorless form on the inside. This is not original to the piece. It is a borosilicate glass form that was created to help connect the reassembled top and bottom sections of the pitcher and support several “floating” fragments, which barely touch the neighboring fragments. In some cases, the fragments don’t touch at all, but a close approximation of their correct location can be determined by the surface decoration.

- Close up of the pitcher in its case in the Glass in the Islamic World Gallery.

- Conservator Stephen Koob reuniting the fragment with the pitcher.

- Pitcher with Animals and Birds, perhaps Iran, 975-1025. Fragment lent by the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – PreuBischer Kulturbesitz Museum fur Islamische Kunst. 59.1.489.

The distinct surface decoration also led to the identification of an additional fragment belonging to this pitcher, but owned by the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin. We don’t know how this one fragment ended up so far away from the rest of the object but, luckily, they were reunited in 2002 when the Museum für Islamische Kunst kindly agreed to a long-term loan of the fragment.

The appearance of this large triangular rim fragment is slightly different than that of the rest of the pitcher likely because of differences in their burial environment or what happened to them after excavation. Can you find the fragment?

Conservation Stories Case

When you walk through the galleries, you may notice that some broken objects, especially those that came from archaeological sites, are not completely restored and have visible losses (missing areas).

Each object that comes to the conservation lab for treatment requires a unique approach because of the condition of the object and the goal of the treatment. Sometimes conservators only stabilize an object, leaving losses visible to present part of the history of the object, or to avoid further damaging a very fragile object through unnecessary handling. Other times, the losses are filled (with a synthetic material) to give an object more structural support or to help make the object more readable for display.

- The Conservation Stories case in the Study Gallery.

- Objects in the Conservation Stories case.

This case in the Study Gallery contains four objects — Bottle [69.1.39], Islamic Pitcher [2007.1.26], Islamic Beaker [74.1.18], Beaker [67.1.19] — that were all conserved to a different degree of completion. The label explains some of the decisions that went into each treatment.

Crizzling Cases

Most people think of glass as a very stable material, and in many ways it is. But it can and does deteriorate. The deterioration of a glass is dependent on two things: its composition and the environment. Most of the glass in the Museum’s collection is stable in our climate-controlled galleries and storage areas. But there are some glasses that are made from such an unstable composition that they continue to deteriorate. These cases in our Study Gallery are dedicated to our most unstable glasses which need an even more tightly controlled environment. Read about another unstable glass in our galleries in this previously published blog post about the Osler candelabrum.

- The Crizzling Cases in the Study Gallery.

- Crizzled objects in one of the Crizzling Cases.

- Detail of a severely crizzled glass.

Invertebrate models of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka

Our conservators have been researching and treating glass models made by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka for almost 20 years, including models in other collections all over the world. Much of what is known about how these incredible, multimedia objects were created, was discovered through careful examination and analysis of the objects themselves. Learn more about the treatments and discoveries that were made during the preparation of the models for the 2016 exhibition Fragile Legacy: The Marine Invertebrate Glass Models of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka in a 2016 blog post, Shedding Light on a Blaschka Model, a 2017 blog post, The Secrets of the glass sea cucumbers, and this video.

- The Blaschka case in the Glass in the 17th-19th Century Europe Gallery.

- Blaschka Nr. 287, Synapta maculata (1885); Synapta maculata (2016), Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, Dresden, Germany, 1885. Lent by Cornell University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. L.17.3.63-8.

- During Treatment. Blaschka Nr. 141, Cladonema radiatum (1885); Cladonema radiatum (2016), Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, Dresden Germany, 1885. Lent by Cornell University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. L.17.3.63-481.

Tiffany window (76.4.22)

This iconic stained glass window made by Tiffany Glass in 1905 had an old repair that yellowed rapidly a few years ago. The treatment was a collaboration between our conservators and a stained glass conservator based in North Adams, Mass. Read about the treatment in this blog post from 2014.

- Window with Hudson River Landscape pre-conservation.

- Detail of the yellowed repair.

- Window with Hudson River Landscape, Louis Comfort Tiffany / Tiffany Studios, Corona, N.Y., 1905. 76.4.22.

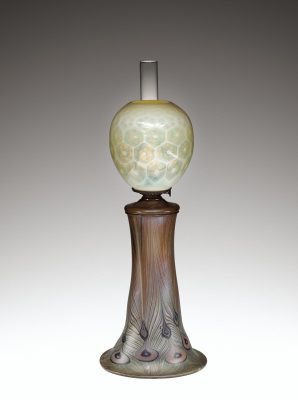

Favrile Kerosene Lamp with Morning Glory Shade and Peacock Feather Base (2006.4.287)

This Tiffany lamp came into the Museum’s collection in 40 fragments and hundreds of tiny chips of glass. It was carefully re-assembled by our Chief Conservator, Stephen Koob. Read about its treatment in this article on Restoring Tiffany.

- Lamp in its case in the Glass in America Gallery.

- The lamp prior to re-assembly

- Favrile Kerosene Lamp with Morning Glory Shade and Peacock Feather Base, Louis Comfort Tiffany / Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, Corona, N.Y., about 1895-1905. Gift of Micki and Jay Doros. 2006.4.287.

Continuous Mile (2013.9.1)

Sometimes conservation is more about preventing damage rather than active treatment. This work by Liza Lou is composed of a stacked and coiled, mile long, cotton rope with millions of glass beads meticulously sewn on with thin cotton threads. It transforms an everyday object into something extraordinary, and many of our visitors want to know what it feels like. Despite being in direct view of our staff, and having a barrier and no touching signs around it, many visitors have reached over the barrier to touch and even lift up the beaded rope. In order to further discourage our visitors from touching this rather fragile sculpture, we asked the artist to create another section of beaded rope for visitors to touch. Our “Please Touch Me” Beaded Loop is secured next to Continuous Mile with a sign encouraging our visitors to touch the loop instead of the artwork itself.

- Continuous Mile, Liza Lou, Los, Angeles, Calif., and Durban, South Africa, 2006-2008. Purchased with special funds provided by Corning Incorporated in honor of the opening of the Contemporary Art + Design Wing, March 2015. 2013.9.1.

- “Please Touch Me” Beaded Loop near Continuous Mile.

- Wear and tear on the “Please Touch Me” Beaded Loop.