This post comes from Morgan Albahary, curatorial and collections assistant of The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass and contributor to the Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics publication.

The “Digital Age” has forever changed the way we research. From the more than 25 million titles available on Google Books, to the nearly 325 million pages scanned and uploaded to Newspapers.com, historians now have unprecedented access to decades’ worth of primary and secondary sources — all at the tips of our fingers. Mining a combination of online sources like these, in conjunction with traditional research methods, I was able to identify over 220 commissions for the Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics appendix — a number that has continued to grow since publication earlier this year.

Design for the First Presbyterian Church of Poughkeepsie,

1906–08. Tiffany Studios. Watercolor, gouache and graphite

and transparent paper, mounted on paper. 17 3/4 x 25 1/2 in.

(45.1 x 64.8 cm). Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld

Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967. The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

67.654.7.

Along with making a staggering number of texts available online, the “Digital Age” has also ushered in a new era of accessibility to photographs — both new and historic. For example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been working toward digitizing their entire collection, including more than 350 design drawings from the studios of Louis C. Tiffany. The digitization of these design drawings, coupled with the ability to zoom in on high-resolution images, has granted researchers not only remote access, but also the ability to closely examine these important works like never before. This unparalleled opportunity helped me to identify the design drawing below as the First Presbyterian Church of Poughkeepsie in Poughkeepsie, New York, which Tiffany’s firm decorated between 1906 and 1908. Although the church has since undergone extensive renovations, parts of the original interior, including 12 mosaic columns supporting the central dome, are still extant today.

Happily, this fervent push towards digitization is no longer restricted to major institutions, but is now common among smaller organizations such as local historical societies, where untold treasures abound. A period newspaper reference to a Tiffany mosaic in Wappinger Falls, New York, spurred me to search for a historic photograph, which I found on their local historical society’s Flickr page. Had the local historical society not scanned and uploaded their photograph collection, I would have never had access to this material. New materials like this are added to these types of sources daily, so it’s important to periodically revisit these sites.

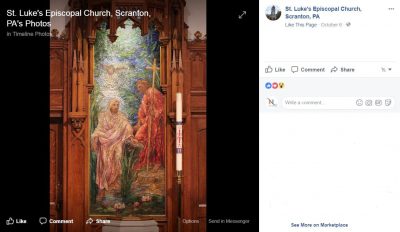

Image-driven social media platforms, such as Facebook, Pinterest, and Instagram, have also democratized the process of research. While many online sources require monthly or yearly subscriptions, these social media platforms are free. Anyone can create an account and upload photos from their camera phone, making social media a new and tantalizing resource for research. For instance, you can follow various “boards” on Pinterest to find period photographs of Gilded Age interiors, or you can even search through “geo tagged” photos on Facebook and Instagram to determine whether a Tiffany mosaic is still extant. A unique feature of the Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics appendix is the inclusion of the current status of each commission (extant, lost, or unknown), which serves to raise awareness of the need for preservation. These types of status designations would not have been possible without the use of social media.

Wappingers Historical Society’s Flickr page, with several galleries containing hundreds of historic photographs scanned and uploaded from their collection.

- Historic photo showing the apse of Zion Episcopal Church in Wappinger Falls, New York, which the Tiffany Studios encrusted in glass mosaic in 1907. Photo source: Flickr.

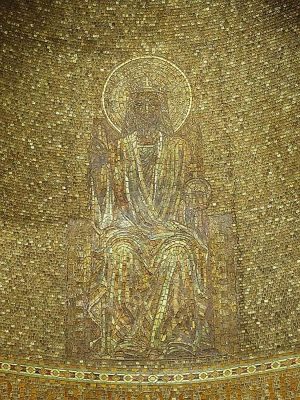

- Detail, chancel mosaic depicting Christ enthroned, 1907. Tiffany Studios. Glass mosaic. Zion Episcopal Church, Wappingers Falls, New York. Photo source: the author.

Without these digital resources, I would not have been able to flesh out the full scope of Tiffany’s mosaic production, which had previously been uncertain. I’m happy to report that I’ve made many subsequent discoveries since the appendix was published. It is my hope that this blog post inspires people to embark upon research projects, equipped with new tools they may have never thought pertinent before. But more importantly, I hope that the appendix brings to light many more Tiffany mosaics either lost, long forgotten, or simply hidden in plain sight.

- A Pinterest board featuring period photographs and renderings of Vanderbilt residences.

- A screenshot confirming the extant status of a Tiffany mosaic in Scranton, Pa., found on the church’s Facebook page. Panel, Baptism of Christ, 1906. Tiffany Studios. Design attributed to Frederick Wilson (British, b. Ireland, 1858–1932). Glass mosaic. St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Scranton, Pa.

Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics is on view at The Corning Museum of Glass through January 7, 2018. Learn more about the exhibition.

1 comment » Write a comment