Mystery. Scandal. Fraud. Like any other cultural institution, the collections within the Rakow Research Library are not immune from tales of secrets long-buried – unsurprising, really, for a library that includes nearly 200 archival collections. For years, I’d heard tell of a scandal involving a Dr. Thomas W. Dyott buried within the boxes of our Glasshouse Money collection. This collection includes 121 paper scrips (a type of credit) used by glassmaking factories to pay their workers.

I resolved to dig deeper to rediscover the story of Dr. Dyott, now nearly 200 years old.

Thomas W. Dyott immigrated to Philadelphia from England in 1805 and soon began selling his own medicinal inventions as a practicing doctor. Business boomed and Dyott expanded his ventures into glassmaking, where he found even more success – so much so that the historical flasks and bottles associated with his tenure in the glass business are some of the most highly-prized among collectors.

- Whiskey Flask with Portraits of Washington and Taylor, Dyottville Glass Works of Thomas W. Dyott, Philadelphia, Pa., 1845-1848. 50.4.508.

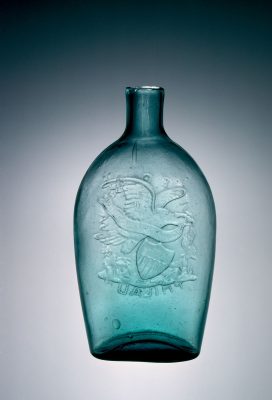

- Eagle Flask, Dyottville Glass Works, United States, about 1850-about 1869. 60.4.169.

Dyott established his Dyottville Glass Factories in the early 1830s and instituted a strict set of moral rules which included – no doubt to the delight of the young boys under Dyott’s employ – fines for the mistreatment of an apprentice. Shorter workdays (with a mid-morning and mid-afternoon break) were given to all, and apprentices were required to attend school and church – an easy task with a church on the premises.

In many ways idyllic, Dyottville was a steep departure from the typical Industrial Revolution-era factory setting. Dyott demanded of his workers decency in character, but also gave it in return. Though profit was without doubt a motivating factor in the establishment of his business model, I would argue that his intentions were at least equally driven by adherence to a strict moral code. How, then, does a person with such a record find himself in the middle of a scandal?

Dyott, eager to expand once again, established the Manual Labor Bank in 1836. He had no experience whatsoever in banking, but nevertheless jumped headfirst into the venture. During this time, a bank could actually produce its own currency, and the Manual Labor Bank did just that. Pictured centrally on this three dollar Manual Labor Bank scrip is a large vignette of a glasshouse interior, possibly a Dyottville factory, in addition to two small portraits, one of Dyott and the other of Benjamin Franklin.

Three dollar promissory note signed by T.W. Dyott and issued to his brother, Michael B. Dyott, 1837. CMGL 165122. Notice the glassblower bedecked in white in the center of the vignette, some argue he looks just like Elvis, but that’s another blog post …

Dyott couldn’t have established his bank at a worse time. The financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837 followed the very next year and it was Dyott’s response to the panic that ultimately led to his demise. Though illegal, Dyott issued scrips of smaller denominations to his grateful employees, who would have otherwise been unable to purchase essential groceries and supplies. But Dyott’s bank couldn’t keep up with the demand and he pleaded insolvency in late 1838. Soon after, he was found guilty of fraudulent insolvency (and other charges, such as conveying money and goods to family members) and was sentenced to three years at Eastern Penitentiary, an upgrade from the possible sentence of up to seven years of hard labor in solitary confinement. After nearly two years behind bars, Dyott received a governor’s pardon and – save for a brief arrest as a debtor after his release from prison – lived out the remaining 20 years of his life a free man, albeit one of much less means.

It turns out the story of Thomas W. Dyott didn’t hold up to the rumored promises of scandal and intrigue. Instead, I seemed to uncover the story of a successful man with good intentions who paid a steep price for his overconfidence.

Curious and Curiouser: Surprising Finds from the Rakow Library is on view at Rakow Research Library at The Corning Museum of Glass through February 17, 2019. Learn more about the exhibition.

3 comments » Write a comment