Imagine your eyes were made of peapods, your nose a pear. In the 16th century, Italian painter and portraitist Giuseppe Arcimboldo represented the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II with just such features. Sometimes known as the “grandfather” of Surrealism (a 20th century cultural movement that married two worlds: fantasy and reality), Arcimboldo used non-human elements, such as fruits, vegetables, animals, and food, to represent the human body. In the 17th century, French engraver Nicolas de Larmessin picked up where Arcimboldo left off. Best known for his serious depictions of French nobility, Larmessin is also known for his series Les costumes grotesques et les métiers (which translates to something like “fanciful trade costumes”). These engravings portray men clad in the tools and wares of their trades. In the 18th century, German engraver Martin Engelbrecht created a similar series, Assemblage nouveau des manouvries habilles (new clothing of tradesmen outfitted in their own works and tools). These prints also depicted individuals dressed in items associated with their profession. Surrealist artists of the 20th century, such as René Magritte, put their own stamps on the imaginative representation of human form in works such as The Difficult Crossing II (1926).

The Rakow Research Library offers several exciting examples of glass-related professions depicted in this centuries-old style, including three late-18th century engravings by Larmessin: Habit de Marchand miroitier lunettier, Habit de verrier fayencier, and Habit de vitrier.

- CMGL_166686 – Habit de Marchand miroitier lunettier, Nicolas de Larmessin, ca. 1680-1700, CMGL 166686

- CMGL_166691 – Habit de verrier fayencier, Nicolas de Larmessin, ca. 1680-1700, CMGL 166691

- CMGL_137235 – Habit de vitrier, Nicolas de Larmessin, ca. 1680-1700, CMGL 137235

Each of these men is outfitted in the tools and wares of his respective trade; among these features are mirrors, eyeglasses, lenses, a telescope, a chandelier, and various pieces of glass and ceramic ware. Based on their costumes, can you guess their trades?

Also in our collection are four prints by Martin Engelbrecht, with titles supplied in French and German: Femme de vitrier/Eine Glaserin, Un vitrier/Ein Glaser, Une verriere/Eine Glassmacherin, and Un verrier/Ein Glassmacher.

- CMGL_129855 – Femme de vitrier/Eine Glaserin, Martin Engelbrecht, 1730, CMGL 129855

- CMGL_129851 – Un vitrier/Ein Glaser, Martin Engelbrecht, 1730, CMGL 129851

- CMGL_129856 – Une verriere/Eine Glassmacherin, Martin Engelbrecht, 1730, CMGL 129856

- CMGL_129853 – Un verrier/Ein Glassmacher, Martin Engelbrecht, 1730, CMGL 129853

These merchants are also themed for their respective trades: glaziers (at left) and glassmakers (at right). Notice the similar colors and outfits of each pair.

Looking for glass seller prints a little less … flashy? We have those, too. The print below (left), Bicchieraro, paints a more realistic picture of a 16th century glass merchant. The original engraving, printed in the late 16th century, is attributed to Annibale Carracci – a member of a Bolognese family of painters, engravers, and etchers which also included brother Agostino and cousin Lodovico. Our print, however, was one in a series reprinted in 1646 in Rome.

- CMGL_166692 – Bicchieraro, Annibale Carracci, ca. 1646, CMGL 166692

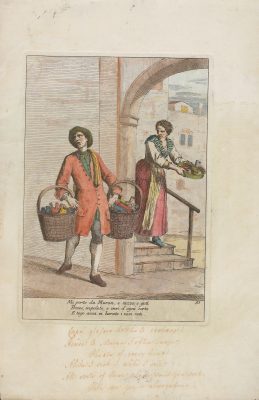

- CMGL_166703 – Mi porto da Muran, Gaetano Zompini, ca. 1750-1778, CMGL 166703

- CMGL_166754 – Madame de Cristaux, Barthélemy-Louis Mendouze, ca. 1835, CMGL 166754

This next engraving (center), printed in the second half of the 18th century, features a man selling colorful glass bottles on a street in Venice. The print, by Italian engraver Gaetano Zompini, is hand-colored and part of a series of prints depicting Venetian merchants.

Madame de Cristaux stands before a counter of wares in this next print (right), also hand-colored. Among items on her counter are vases, bowls, a clock, and a glass dome containing flowers. This print was part of the Genre Parisien series created in the early 19th century by French printer Barthélemy-Louis Mendouze.

The prints included in this post are not the only ones which feature glass sellers in our collection. Stop by the Rakow Research Library to see more – some are even on display in our current exhibition, Curious and Curiouser: Surprising Finds from the Rakow Library, which is open through February 17, 2019.

Curious and Curiouser: Surprising Finds from the Rakow Library is on view at Rakow Research Library at The Corning Museum of Glass through February 17, 2019. Learn more about the exhibition.