Textile conservator and Ph.D. candidate Charlotte Holzer recently conducted research at The Corning Museum of Glass on the history and conservation of handmade glass fibers. Holzer is a 2016 recipient of the Museum’s Rakow Grant for Glass Research, established in 1986 to foster scholarly research in the history of glass and glassmaking from antiquity until the mid-20th century, from anywhere in the world. I checked in with her to find out a little bit about what she was working on during her time in Corning.

Textile conservator and Ph.D. candidate Charlotte Holzer recently conducted research at The Corning Museum of Glass on the history and conservation of handmade glass fibers. Holzer is a 2016 recipient of the Museum’s Rakow Grant for Glass Research, established in 1986 to foster scholarly research in the history of glass and glassmaking from antiquity until the mid-20th century, from anywhere in the world. I checked in with her to find out a little bit about what she was working on during her time in Corning.

How did you become interested in glass fiber*?

My curiosity in glass fibers began when a colleague in the Bavarian National Museum Munich (BNM) told me that we had a late-19th century dress made of the material. She knew I was interested in mineral fibers and that I was always looking for challenging conservation projects. I soon found out that neither textile nor glass conservators have seriously considered glass fibers as research fields. That’s when I decided to start a Ph.D. at the Technical University in Munich on the conservation of historic glass fiber textiles.

- The famous glass dress royal robe of Princess Eulalia, Libbey Glass Company, [1893]. Gift of Rob Smith. CMGL 134150. Visitors can learn more about fiberglass fabric and see fiberglass textiles and images in our 2017 exhibition, Curious & Curiouser: Surprising Finds from the Rakow Library.

- The famous glass dress royal robe of Princess Eulalia, Libbey Glass Company, [1893]. Gift of Rob Smith. CMGL 134150. Verso of cabinet card. Visitors can learn more about fiberglass fabric and see fiberglass textiles and images in our 2017 exhibition, Curious & Curiouser: Surprising Finds from the Rakow Library.

Tell me about the Infanta Eulalia dress from the Deutsches Museum that you’ve been researching.

The glass dress is a rich evening gown, fashionably tailored in the style of 1893 with a full-length, trained skirt and low-cut bodice. The outside is covered with a fabric made from white glass fiber and silk, and decorated with braids and fringes, the lining is a beige silk taft. It was produced by the Libbey Glass Company in Toledo, Ohio, for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and presented to the Spanish Infanta Eulalia upon her visit. In 1924, Eulalia’s sister donated the dress to the Deutsches Museum. It has never been on display and, around 1990, was transferred to the BNM to improve storage conditions. When I started my research, only the skirt and some loose fringes were preserved, it was soiled, the silk lining degraded, and the glass fiber textiles damaged with tears and holes. The dress’ condition might be a result of heavy bombing of the museum buildings during WWII and the use of the storage area as an air raid shelter.

What made you decide to conduct your research in Corning?

During my search for glass fiber objects that were similar to the dress in manufacturing technique and date, I came across the online collection database of The Corning Museum of Glass. From there, I discovered the amazing facilities at the Rakow Research Library. The Deutsches Museum, where I was a Scholar-in-Residence at the time, supported a short research trip there in May. By then I had been awarded the Rakow Grant for Glass Research 2016, which enabled me to come back in October to examine damage patterns on glass fibers and test cleaning methods in the Museum’s world-renowned glass conservation laboratory.

How are glass fibers made and turned into flexible cloth or threads?

The fibers we are talking about are produced by flameworking: a glass rod is heated to a workable temperature and drawn into minute fibers with a diameter of 10 to 40 micrometres. The end of the fiber is fixed to a rotating wheel using a pair of tweezers and thereby endless filaments can be produced when the glass rod is fed continuously into the flame. After finishing this process, the bundle of glass fibers is cut and taken off the wheel. [Note: You can see CMoG flameworker Eric Goldschmidt spinning glass threads in this Instagram video.]

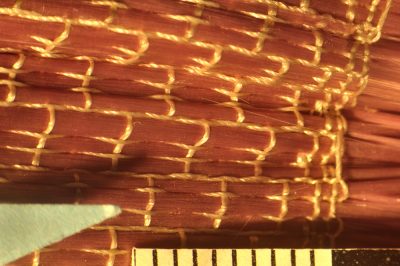

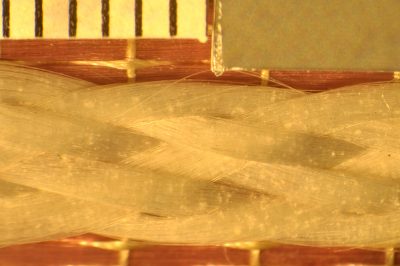

For most historic glass fiber textiles, traditional hand looms were covered with silk, cotton, or hemp and then the glass fiber inserted either as main weft or as decorative cloth component. Often, organic fibers were put between the glass fiber threads, to protect them from mechanical damage caused by the weaving tools. To produce neckties or belts, bundles of glass fibers were braided by hand. Twisted threads only appeared around 1900, when fibers could be processed fine enough not to break. I presume it was also then, that the manufacture of pure glass fabrics started, because earlier examples are not known so far.

Doll with glass fiber kimono made by the Libbey Glass company for the 1893 Chicago’s World Fair (77.4.89). The lavender/pink of the doll’s kimono as well as the white sash and the black hair are made from glass fibers.

How fragile are the glass fiber objects?

Single glass fiber filaments in woven textiles or braids can break from minimal mechanical strain. That includes the accumulation of encrusted soiling, the application of pressure from certain cleaning procedures, as well as moving an object without sufficient support. However, not all broken filaments come off and get lost, but most are still stuck in the fiber bundles.

Another damage phenomenon I could observe on historic glass fibers from different manufacturers are white crystals building up on the surface. This form of glass deterioration is often connected to soluble components in the glass, like alkalis, added for better workability, that migrate to the surface, where they react with the humidity and pollutant gases in the air.

- Photomicrograph of the doll (77.4.89) showing use of organic threads (white) and glass fibers (lavender/pink).

- Photomicrograph showing glass deterioration in the form of white crystals on the surface of the doll’s (77.4.90) white glass fiber sash. Interestingly, the lavender glass fibers, which must have a different composition, are not deteriorating.

Considering its fragility, why would someone make an object out of glass fibers?

I can only speculate on the makers’ motivations, but to me it seems the driving factors were curiosity and the desire to create something rare and beautiful that attracts attention.

Lampworkers fascinated their audience with the so-called glass spinning process for centuries and, of course, produced purchasable objects on the way. Textile manufacturers were experimenting with different materials, including glass, for synthetic fibers. For decorative textiles for interiors or dresses, very practical reasons came into play: metal threads used to weave rich damasks darken, while glass fibers shine and glitter in the light. In the late 19th century, hand-drawn glass fibers were also appreciated and used for their technical properties, such as chemical resistant filters, warmth retaining rheumatism wool, or heat-proof insulation.

* Glass fiber: A generic term to designate any fiber drawn as thread from molten glass, regardless of its form, appearance, method of manufacture or ultimate purpose.

— from Newman, Harold: An Illustrated Dictionary of Glass, Thames and Hudson, London 1977, p. 134.

Interested researchers who work in disciplines that intersect with glass research, including archaeology and anthropology, art history, conservation, and the history of science and technology, may apply for a Rakow Research Grant online. Applications for 2017 are due by Feb. 1, 2017.

![The famous glass dress royal robe of Princess Eulalia, Libbey Glass Company, [1893]. Gift of Rob Smith. CMGL 134150.](https://oldblog.cmog.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/rakow_cabinet_card_02-271x400.jpg)

![The famous glass dress royal robe of Princess Eulalia, Libbey Glass Company, [1893]. Gift of Rob Smith. CMGL 134150. Verso of cabinet card.](https://oldblog.cmog.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/rakow_cabinet_card_01-268x400.jpg)