![Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), 1680 Jan Verkolije Oil on canvas [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blog.cmog.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/antonie_van_leeuwenhoek_portrait-337x400.jpg)

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), 1680

Jan Verkolije

Oil on canvas

[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) was a Dutch scientist best known for his work on the improvement of the microscope. From there, separating fact from fiction can be tricky. Key aspects of his career are uncertain: When did he start using microscopes? How did he make his lenses? Did he really craft hundreds of microscopes, as he claimed, or was this self-promotion? Some of these question have been resolved – we now know how Van Leeuwenhoek made lenses, but others remain.

One enduring mystery of van Leeuwenhoek’s life is whether or not he knew his contemporary, painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Their lives are seemingly intertwined. They were born within a week of each other in October of 1632 in Delft, a small, but cosmopolitan city of 20,000 known for its tapestries, pottery, tiles and paintings. They lived within blocks of each other. The connection is so strong that many have pondered the implications of these giants of 17th century art and science being acquaintances: the conversations they might have had, their influence on their work. Yet, there is no conclusive evidence they knew or even met each other.

But, they must have known each other. How could the extraordinary work they were doing escape the other’s notice? This nagging notion has led historians to seek conclusive evidence linking van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, a search that has turned up several clues.

Delft’s Market Square as it looks today, Delft’s City Hall,

the Stadhuis where van Leewenhoek worked for several years

is at the end of the square. (“A view of Delft Central Market

Square with the Town Hall,” 4 May 2009, Herebedug.

Wikimedia Commons)

Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer lived within walking distance of each other just off Delft’s central Market Square. The tavern Vermeer owned, the Mechelen Inn, was on the square, its front visible from the Stadhuis, Delft’s City Hall, where van Leeuwenhoek worked as a city official. Could van Leeuwenhoek have stopped by the Inn for a drink after work?

The two men had friends in common, including Constantijn Huygens, an influential diplomat, artist, and poet who possessed a keen interest in microscopy and the natural sciences. Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer also shared an interest in optics and lenses. Van Leeuwenhoek made the lenses he used in his microscopes, carefully guarding his secrets. Many art historians believe Vermeer used lenses to achieve the photographic quality observed in his paintings. Could they have discussed optics with their circle of friends?

Simple microscope, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek,

Delft, the Netherlands, c. 1675 – 1723.

Lent by Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Image Courtesy of Museum Boerhaave.

One piece of historical evidence puts van Leeuwenhoek in direct contact with Vermeer, albeit posthumously. After Vermeer’s death in 1675, van Leeuwenhoek was appointed executor of Vermeer’s estate. This might indicate they were friends, but the circumstances around van Leeuweenhoek’s appointment are unclear. His appointment as Vermeer’s executor may have been job-related. Van Leeuwenhoek managed several estates as a city official. Records indicate van Leeuwenhoek worked diligently to reconcile Vermeer’s estate, seemingly in an even-handed manner. Some of his actions benefited Vermeer’s widow – his reclamation of several of Vermeer’s paintings, for instance. But, he also took steps to pay off Vermeer’s creditors, arguably to the detriment of Vermeer’s widow and children.

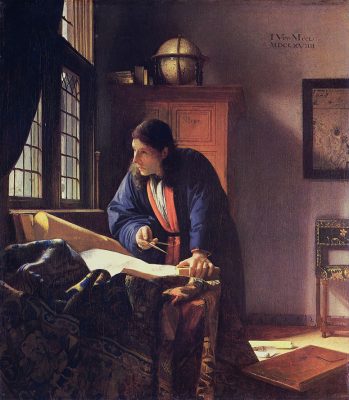

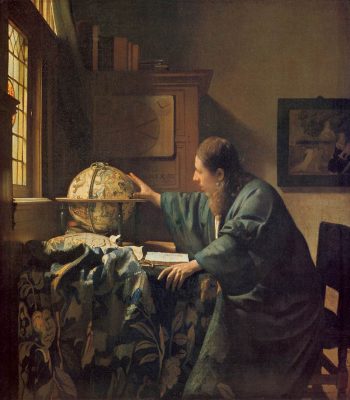

The tenuous nature of the evidence has not prevented speculation of their relationship. One fascinating suggestion is that van Leeuwenhoek actually posed for two of Vermeer’s paintings: The Geographer (1668-1669) and The Astronomer (1668). Do similarities between the model in the paintings and contemporary portraits of van Leeuwenhoek, most notably Cornelis de Man’s portrait in The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Gravezande suggest Vermeer’s model is a romanticized van Leeuwenhoek? When Vermeer painted the works, van Leeuwenhoek was a surveyor who was becoming known for his scientific work. The paintings depict instruments and books that van Leeuwenhoek would have used in his work as a surveyor and scientist. Could van Leeuwenhoek be the person in both paintings?

- The Geographer, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), 1668-1669, Städelsches Kunstinstitut Museum

- The Astronomer, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), 1668, Louvre, Paris

- The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Gravezande. Cornelis de Man, 1681. Gravesande is holding the scalpel. Van Leeuwenhoek is standing to his left with his hand over his chest.

Until someone in Delft discovers a letter in their attic from Vermeer to van Leeuwenhoek or a similarly revealing document comes to light, we will never know with certainty whether or not the two men knew each other. But, there is enough circumstantial evidence to make one imagine what interactions and conversations these giants of art and science may have had.

Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope is open 9 am – 5 pm every day through March 19, 2017. This exhibition tells the stories of scientists’ and artists’ exploration of the microscopic world between the 1600s and the late 1800s. Unleash your sense of discovery as you explore the invisible through historic microscopes, rare books, and period illustrations, and take a #cellfie in the Be Microscopic interactive.

1 comment » Write a comment