This post comes from Laura Hashimoto and Bonnie Hodul, Rakow Research Library interns who worked on the conservation of the Whitefriars stained glass cartoon collection over the summer of 2016, in conjunction with West Lake Conservators. Read more about this project and the collection in previous posts.

Laura and Bonnie here, bringing you one last post as we close out our summer working on the Whitefriars stained glass window cartoon conservation project at the Rakow Research Library. As you may know, the Whitefriars collection consists of a total of 1,800 rolls, holding an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 individual objects. It was fantastic to work on just a small selection of such a large collection of interesting works made by the Whitefriars glass company.

This summer, we treated 62 individual cartoons from 11 different rolls in the collection, which depicted designs for stained glass windows that span the globe. In total, we treated approximately 948 square feet of paper, canvas, and photographs, on both the front and back.

We selected rolls with a focus on locations that we could reach out to, connect with, and visit, as well as locations from far reaching continents to gain a better understanding of the scope of the stained glass windows made by the Whitefriars Company. Many of the rolls we worked on this summer were for churches in England, where the Whitefriars company was based, including St. Albans Church, St. Vedast’s Church, and St. George’s Church in London, as well as St. Peter’s Church in Bristol, and St. Nicholas’ Church in Norfolk. We also treated a roll for St. Mary’s Church in Ajmer, India, Calvary Episcopal Church in New Jersey, as well as the National War Memorial in New Zealand, and a roll for Temple Emanu-El, a synagogue in New York City.

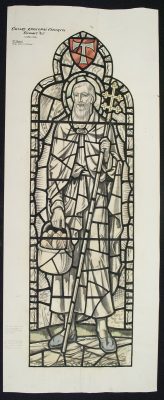

- Wove paper cartoon for St. Alban’s Church, London, England, BIB#148612.

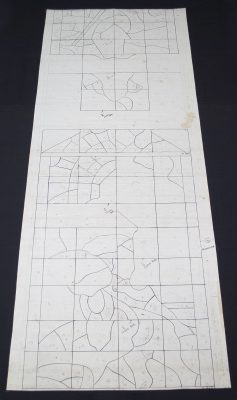

- Tracing paper cartoon for St. Peter’s Church, Bristol, England, BIB#163464.

- Gelatin silver photograph cartoon for St. Peter’s Church, Bristol, England, BIB#163471.

- Gelatin silver photograph cartoon for St. George’s Church, London, England, BIB#164000.

- Wove paper cartoon for Calvary Episcopal Church, New Jersey, USA, BIB#147836.

- Wove paper cartoon for Temple Emanu-El, New York City, USA, BIB#163463.

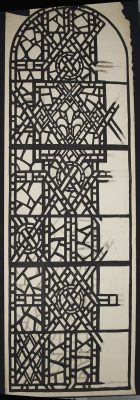

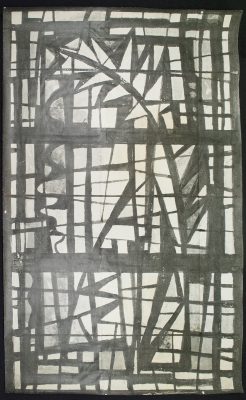

- Waxed canvas cartoon for St. Vedast’s Church, London, England, BIB#161865.

- Wove paper cartoon for St. Mary’s Church, Ajmer, India, BIB#163923.

- Gelatin silver photograph cartoon for the National War Memorial, New Zealand, BIB#163462.

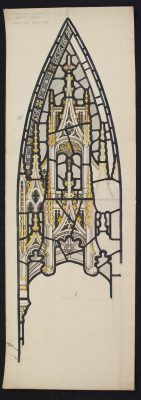

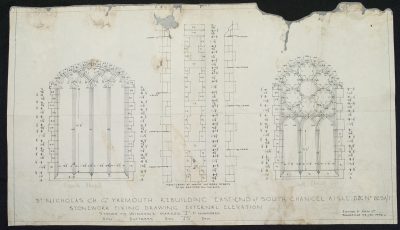

- Architectural drawing on paper for windows in St. Nicholas’ Church, Norfolk, England, BIB#163443.

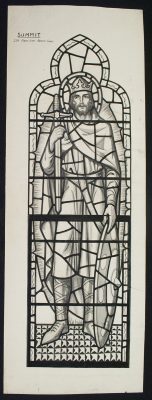

We also searched for unique materials and techniques, including materials that had not been encountered in the project so far, and for specific artists such as Pierre Fourmaintraux and Alfred Fischer who worked as designers for the company. Fourmaintraux used the dalle de verre process for his stained glass windows and interesting methods for producing his cartoons. Fischer was one of the last stained-glass window designers to work for the company before its closure in 1980.

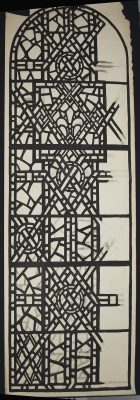

We found examples of materials commonly used for cartoons, such as a thicker wove paper for design drawings that helped the artists transfer the detail of the design onto the glass pieces that would make up the final window. We also found many waxed canvases, which were used for cutting out the glass shapes and the final lead-work that would hold the window together.

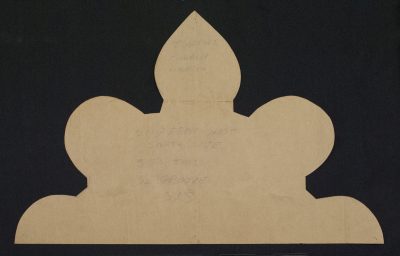

Aside from these more typical materials, we also found gelatin silver photographs, which were used starting in the mid-1900s as photographic paper became available at larger sizes. This allowed stained glass window artists to more quickly scale their small drawings up to the full-scale size of the final window. We also found tracing papers, which seemed to have been used in a similar manner to the waxed canvases, but their transparency allowed the designs to be transferred easily through tracing. We worked on objects made of kraft paper, which was often used to cut out an exact template for the intricate shapes of the tops of the windows, and we worked on paper with architectural drawings of the buildings, which had dimensions of where the stained glass windows would be incorporated into the structures.

- Gelatin silver photograph cartoon with applied corrective media made for St. Peter’s Church, Bristol, England, BIB#147489.

- Thick wove paper cartoon made for Calvary Episcopal Church, New Jersey, USA, BIB#163977.

- Waxed linen canvas cartoon made for St. George’s Church, London, England, BIB#163998.

- Kraft paper object made for St. Nicholas’ Church, Norfolk, England, BIB#163966.

- Tracing paper cartoon with applied color made for St. Mary’s Church, Ajmer, India, BIB#147185.

What was incredibly fun was to match our cartoons to presentation drawings held by the Museum of London. In the case of St. Peter’s Church, the Museum of London was able to provide us with photographs of the presentation drawings in their collection so we could actually piece together four stages of the stained glass window making processes used by Pierre Fourmaintraux.

Left: Tracing paper cartoon for “The Nativity,” St. Peter’s Church, Bristol, England, BIB#147807.

Left-Center: Gelatin silver photograph cartoon for “The Nativity,” St. Peter’s Church, Bristol, England, BIB#163468.

Right-Center: Design drawing belonging to the Museum of London, Photograph © Museum of London, courtesy Alex Werner, Head of History Collections.

Right: A photograph of the dalle de verre stained glass window installation at St. Peter’s Church, Lawrence Weston, Bristol, England, courtesy of poster Mike CB

In some of the rolls we treated, we encountered objects that showed us a few different steps of the stained glass window making process, such as the roll for St. George’s Church, which had both photographs as well as waxed canvas cartoons; and Calvary Episcopal Church, which had waxed canvases and wove paper cartoons. Through these matching cartoons used for different parts of the process, we could see the artists’ methods for making the final stained glass windows.

We also made direct connections with Temple Emanu-El and Calvary Episcopal Church, where we were able to see in person the stained glass windows that matched our cartoons.

- Stained glass window and paper cartoon from Temple Emanu-El, New York City. BIB#163463.

- Stained glass window and paper cartoon from Temple Emanu-El, New York City. BIB#163463.

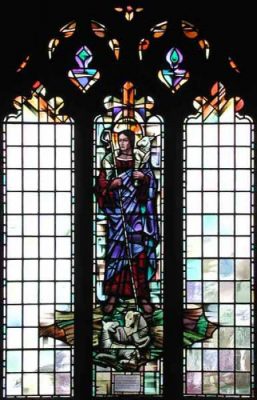

- A photograph cartoon matched to the window it was used to create in St. George’s Church, London, England. BIB#164000.

- A photograph cartoon matched to the window it was used to create in St. George’s Church, London, England. BIB#164000.

A major part of the Whitefriars project is also to connect these amazing cartoons to the institutions that have the stained glass windows the drawings were used to create, as well as to form a dialogue about the Whitefriars company and the process of making stained glass windows. We hope to inspire you to learn more about this wonderful process, and to learn from you in turn with information you may have connected to the project. We’re keeping a lookout for the Whitefriars monk in the corner of any stained glass we see. It’s always a treat when we find an installation match with the paper objects we unrolled in the lab, such as this recent match we found for a paper cartoon with its stained glass window at Christ Church in Short Hills, New Jersey.

Continue to follow The Corning Museum of Glass on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and connect with us as we continue this project into the future! We’re finished with our phenomenal three months working on the Whitefriars Collection, but the project will long outlive us. We hope you are as excited as we are to see where it goes next!

2 comments » Write a comment