This post comes from Laura Hashimoto and Bonnie Hodul, Rakow Library interns who are helping conserve the Whitefriars stained glass cartoon collection over the summer in conjunction with West Lake Conservators. Read more about this project and the collection in previous posts.

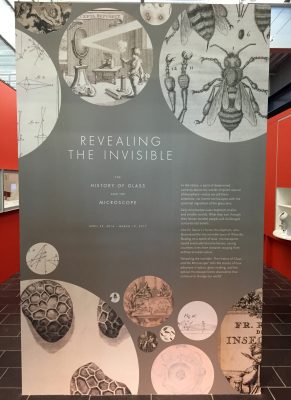

We were thrilled to discover that our summer internship coincided with the Rakow Research Library’s exhibition Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope, which showcases the microscope and its evolving forms from the 17th to 20th centuries! In addition to going on a behind-the-scenes tour with one of the exhibition’s curators, we are fortunate enough to work among these fantastic objects each day. By bringing together rare books and archival material from the Rakow’s collection, didactics explaining innovative applications of glass in the scientific community, and displays of the various microscopes that have been created over the past few centuries, this exhibition really got us thinking about how these tools come into play in conservation.

- Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope

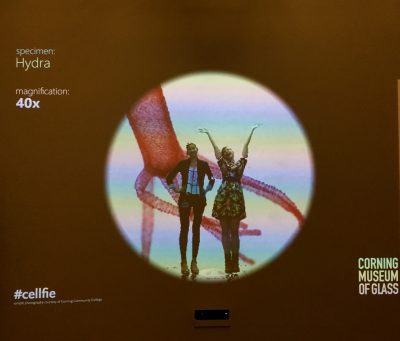

- We played around with one of the many interactive parts of the exhibition, taking some nice #cellfie shots!

As we open up a fraction of the approximately 1,800 Whitefriars rolls, we have come across a fantastic variety of materials, or “primary substrates.” The primary substrate is the material that holds the media on the surface of the drawing. We have seen beeswax-impregnated linen/cotton canvas, machine-made thick paper, kraft paper, tracing paper, photographic paper, and some unfamiliar substrates! The media on the surface of these materials has also been varied, and includes graphite, wax pencils, chalky materials, inks, and paints. These materials all hold important information about the Whitefriars’ stained glass window-making process. For example, many of these objects were used directly underneath stained glass, and needed to be robust enough to withstand this heavy manipulation. While the overall conservation treatment aims are the same for each type of substrate—surface cleaning, humidification, flattening, and tear mending/stabilization—these different materials and their interaction with the various media on the surface inform our treatment procedures.

- Bonnie tries out a replica of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s simple microscope in the Preservation Lab. The exhibition at the Rakow Library is lucky to have one of his simple microscopes on loan from the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, in the Netherlands. Visitors can also have the chance to try out the replica version, and peer through the small hole to look for the pinpoint tip, which would hold a tiny piece of an object.

- Bonnie tries out a replica of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s simple microscope in the Preservation Lab. The exhibition at the Rakow Library is lucky to have one of his simple microscopes on loan from the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, in the Netherlands. Visitors can also have the chance to try out the replica version, and peer through the small hole to look for the pinpoint tip, which would hold a tiny piece of an object.

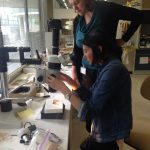

Alongside the logistics detailed in our first blog post, where we looked at the BIG picture, we also need to focus on the tiny, microscopic picture to grasp a better understanding of the materials we encounter in conservation. Fortunately, Astrid van Giffen, associate conservator in the Museum’s glass conservation lab, let us make use of the lab’s Leica Wild M8 stereomicroscope!

- Astrid van Giffen shows us how to set up the Leica Wild M8 stereomicroscope with one of our samples.

- Taking photomicrographs of samples in the Corning Museum of Glass’s Glass Conservation Lab.

- One of the objects we were interested in seeing close up!

Check out what we saw in the photomicrographs we took!

- Thick wove paper and black media under 6x magnification.

- Thick wove paper and black media under 25x magnification.

- Thick wove paper and black media under 50x magnification.

This black media is somewhat friable, meaning it is prone to being easily removed from the paper substrate. When we surface clean these kinds of objects, we are very careful not to disturb it, and clean only areas around the media!

- Thick wove paper and residual cellophane tape adhesive and staining under 6x magnification.

- Thick wove paper and residual cellophane tape adhesive and staining under 25x magnification.

This adhesive came off the plastic tape carrier and embedded itself in the paper substrate, which over time yellowed, darkened and stained!

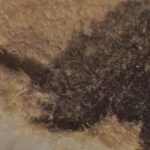

- Beeswax-impregnated canvas and graphite under 6x magnification.

- Beeswax-impregnated canvas and graphite under 25x magnification. This area shows a frayed edge of the canvas.

- Beeswax-impregnated canvas and graphite under 50x magnification.

These waxed canvases were featured in our last post, and were used and handled heavily in the stained glass window process. It was interesting to see how much the wax filled in the weave of the canvas fibers.

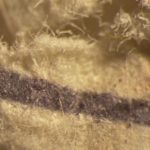

- A torn area on architectural wove paper with black media under 6x magnification.

- A torn area on architectural wove paper with black media under 25x magnification.

- A torn area on architectural wove paper with black media under 50x magnification.

This object is made of a very soft, thin paper with quite a bit of structural damage.

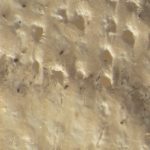

- Kraft paper and graphite under 6x magnification.

- Kraft paper and graphite under 25x magnification.

- Kraft paper and graphite under 50x magnification.

This kraft paper is brown and rough, quite different from the other paper substrates we have seen.

- Tracing paper and graphite under 6x magnification.

- Tracing paper under 25x magnification.

- Tracing paper under 50x magnification.

This tracing paper is smooth, transparent, and very brittle, which means we need to handle it very carefully.

- Tracing paper area with burn/accretion-like hole under 6x magnification.

- Tracing paper area with burn/accretion-like hole under 25x magnification.

- Tracing paper area with burn/accretion-like hole under 50x magnification.

The tracing paper objects also have a number of these dark brown areas that resemble burns through the paper. They are part of the stained glass window-making process and how these tracing papers were used, but we are not sure about their exact origin, nature, or composition.

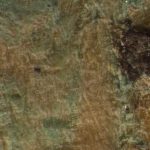

- Tracing paper area with green accretion under 6x magnification.

- Tracing paper area with green accretion under 25x magnification.

- Tracing paper area with green accretion under 50x magnification.

There is a green accretion on one of the tracing papers, which may be a corrosion product from a metallic inclusion (i.e. a metal oxide that has formed), although further analytical testing is required to confirm this.

- Silver gelatin photograph under 6x magnification.

- Silver gelatin photograph under 50x magnification.

This tear on a silver gelatin photograph shows the unique layers present in a photograph. The glossy top layer that holds the light and dark areas of the image is the photograph’s emulsion layer, which appears very different from the fibrous paper substrate support underneath it, seen here at the right edge of the top image at 6x magnification.

Microscopes and the microscopic world are integral to the field of conservation, and we certainly enjoyed bringing the two together for the Whitefriars’ stained glass window cartoon conservation project.

Zooming in and getting to know the objects with the Leica Wild M8!

Follow the progress of the project and learn more about our interns, Laura and Bonnie.

The Rakow Research Library is open to the public 9am to 5pm every day. We encourage everyone to explore our collections in person or online. If you have questions or need help with your research, please use our Ask a Glass Question service.