Scientist Robert Hooke (1635-1703) was passionately curious, had an instinctive understanding of science, and was endlessly inventive. As Curator of Experiments for the recently formed (and soon-to-be-renowned) Royal Society of London, Hooke performed scientific demonstrations for the membership. His microscope presentations, which revealed microscopic details of tiny objects (e.g. the features of a flea), were particularly successful and colleagues insisted he do several at each meeting. These demonstrations, and the illustrations they yielded, became the basis of Hooke’s Micrographia (1665), the first book dedicated to observations of objects under a microscope.

Micrographia, with its ingenious concept, witty observations and beautiful illustrations, caused a sensation and inspired others to take up the microscope. Among them was Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who several years later would first observe microscopic life forms.

Trained in painting, Hooke took particular care with his illustrations, viewing each object from several angles to ensure he drew them accurately. To translate these images to the book, he employed a popular method of the time – using etched metal plates to print illustrations.

Etching as part of the print-making process started in the late 1400s, shortly after Johannes Gutenberg’s (1398–1468) invention of the printing press. Micrographia’s metal plates were made using a process called copper plate etching. A copper plate was covered with a waxy substance resistant to acid. The artist drew the image by scratching the wax with a pointed etching needle. Each scratch exposed the metal underneath, making it vulnerable to the acid. Once the drawing was completed, the metal plate was either dipped in acid or had acid washed over it. The acid dissolved the metal where it was exposed, making an impression and transferring the image to the plate. The remaining wax was cleared, the plate was inked and put through the printing press together with a sheet of paper (often moistened to soften it). The paper picked up the ink from the etched lines, making a print.

Several hundred copies of a print could be made from a plate before it began to show signs of wear.

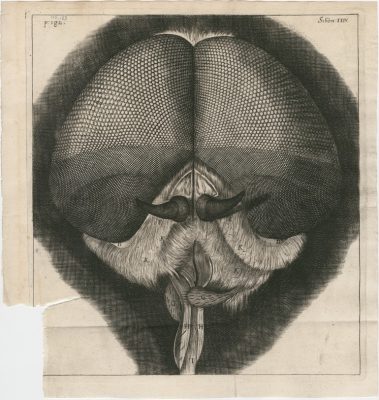

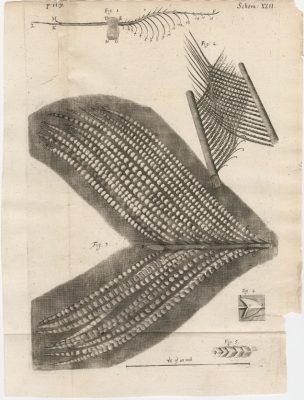

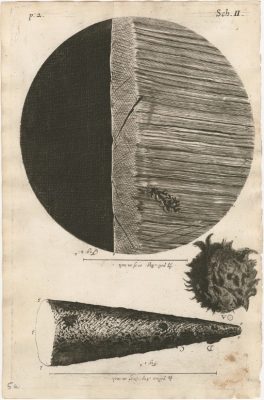

Several artists created the plates for Micrographia, working under Hooke’s close supervision. Their artistry is reflected in the beautiful illustrations – most famously in the flea, but also in the eye of the gray drone fly, on the edge of a razor and point of a needle, and in the details of a feather.

- Illustration from Micrographia (London, 1665), Robert Hooke.

- Illustration from Micrographia (London, 1665), Robert Hooke.

- Illustration from Micrographia (London, 1665), Robert Hooke.

Two editions of Micrographia were published in Hooke’s lifetime using the original plates. By the time the second printing was done in 1667, Hooke was focused on assisting architect Christopher Wren and others in rebuilding London after the Great Fire of 1666. The copper plates were stored for over seventy-five years, until Henry Baker, a popularizer of microscopes like Hooke, discovered and reprinted Hooke’s plates in his Micrographia Illustrata (1746).

Hooke’s ingenious Micrographia still inspires today. A scientific milestone, Micrographia marks a moment when scientists turned their attention to the microscopic and discovered a previously unseen world.

Source: Hooke’s Books: Books that influenced or were influenced by Robert Hooke’s Micrographia

Suggestions for further reading on Hooke’s Micrographia, microscopy and microscopists can be found on the Rakow Research Library’s Microscopes subject guide.

See the Micrographia on display in the Rakow Research Library’s exhibition Revealing the Invisible: The History of Glass and the Microscope, on display April 23, 2016 to March 19, 2017.

The Rakow Research Library is open to the public 9am to 5pm every day. We encourage everyone to explore our collections in person or online. If you have questions or need help with your research, please use our Ask a Glass Question service.