This post comes from Dr. Karol B. Wight, President and Executive Director of The Corning Museum of Glass. Ennion and His Legacy: Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome, the largest exhibition to date devoted to ancient mold-blown glass, is on view until January 4, 2016. Read more about Ennion in Dr. Wight’s first, second, third, and most recent posts in this series.

In antiquity, as today, vessels were made as souvenirs to commemorate a specific event or personal journey.

Sports cups depict gladiators in combat or chariots racing in competition. Just as today’s sports fans buy memorabilia related to a team or individual, so did the ancient Romans. The individual gladiators are sometimes identified by name, as are the teams of horse-drawn chariots. The majority of the mold-blown vessels related to sports competitions are drinking cups.

Religious pilgrimages were commemorated by the pilgrim with the purchase of a mold-blown vessel designed with religious symbols, either Christian or Jewish. Most of the vessels with religious symbols were hexagonal or octagonal, and a cross or menorah often decorated one or more of the vessels’ sides. These vessels were often formed as pitchers or large flasks. They could have held holy water or oil, or they could have been used to pour wine in a ceremony.

Sports Cups

Gladiators were the star athletes of the ancient world. They were befriended by emperors and senators, their achievements were recorded in historical texts, and their fans scrawled their names as graffiti on the walls of cities. Gladiators were immortalized by their depictions in ancient art—wall paintings, marble reliefs, statues, and vessels made in a variety of materials. Vessels, including glass cups, were purchased as souvenirs by fans when they attended a gladiatorial contest at their local arena.

Today’s Formula One and NASCAR races attract the same kind of fan base as chariot racing did in antiquity. Chariot drivers and their horses were known, and teams were named for animals or mythical creatures that embodied strength and prowess, just as sports teams are today. Chariot teams were also identified by colors. Ancient writers have written about the Greens and the Blues, for example.

Both gladiator and chariot cups contain inscriptions in their mold designs that record the names of the gladiators or the chariot teams and drivers. Almost all of these inscriptions are written in Latin, indicating that the artisans creating the molds lived in the western part of the Roman Empire, where Latin was the spoken language. The presence of inscriptions also indicates that the moldmakers could read and write. Whether the buyers of these cups were also literate is not known.

Fighting gladiators pair off on this wine cup, and they are identified by name. Spiculus stands above the fallen Columbus; Calamus and Holes fight; Petraites attacks Prudes, who loses his shield; and Proculus defeats Cocumbus and holds a victor’s palm frond. The armor worn by the gladiators identifies their combat specialty. The helmets, shields, and weapons were each designed for a specific type of combat.

Inscription Cups

Mold-blown cylindrical cups with inscriptions were created primarily for drinking. The mottoes exhort the drinker to rejoice, to be merry, or to live a long life. Other inscriptions are associated with sports because they are related to competition, such as “Seize the Victory!”. All of these inscriptions are written in Greek, which suggests that the mold designers came from the eastern Roman Empire, where Greek was the common language. But because these cups have been found throughout the empire, it is likely that those who used them could read both Greek and Latin.

Most of the cups were made with three-part molds, one section for the base and two sections for the sides. It was common practice for the moldmakers to put a decorative palm frond where the two side molds joined in order to conceal the seam line that showed in the glass when the vessel was inflated. A similar tactic of using palm fronds to conceal mold seams was followed by Jason, Meges, and Neikais, glass artisans who, like Ennion, added their name to their mold designs.

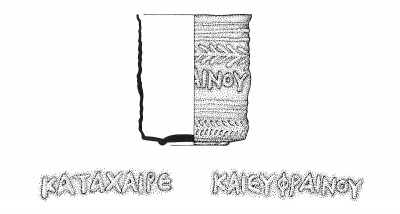

- Beaker with Greek Inscription, Roman Empire, 1-99. 59.1.79.

- Sketch of the inscription in Greek with the words “KATAXAIPE KAI EYΦPAINOY” (Rejoice and be merry)

“Katakaire” Beakers

One type of drinking cup is inscribed in Greek with the words “KATAXAIPE KAI EYΦPAINOY” (Rejoice and be merry). Below two horizontal lines, palm fronds form a wreath above the inscription, while a chevron pattern below two horizontal lines decorates the bottom of the cup. The words of the phrase are divided between the two halves of the glass mold, and the moldmaker concealed the seams by adding vertical palm fronds at the junction of the two mold halves. This use of vertical palm fronds to conceal mold seams can be seen on other beakers with different inscriptions and shapes, which suggests that all of these beakers may have been produced in the same workshop.

Cup with Greek Inscription: “EYΦPAINOY EΦωПAPEI”

(Be glad that you are here), Roman Empire, 1-99. 72.1.3.

“Be Glad That You Are Here”

Another type of drinking cup is inscribed in Greek with the phrase “EYΦPAINOY EΦO ΠAPEI” (Be glad that you are here). Scholars believe that cups such as these, as well as the “Katakaire” beakers, would have been used at social gatherings to welcome guests and to ensure their well-being and contentment. Such cups were used to drink wine, so these sentiments are quite appropriate.

Mold-Blown Glass for the Marketplace

When materials needed to be shipped across the Roman world, mold-blown glass vessels became a natural solution for merchants. Because mold-blown vessels could be made to the same size and had a consistent interior volume, goods such as olive oil and wine were frequently shipped in them. For the customer, glass bottles enforced governmental standards of weight and volume. One could see how much oil or wine the bottle contained, and the seller had no opportunity to cheat the consumer. While the majority of these bottles are four-sided, others were designed to imitate the wooden barrels and clay vessels that were also used to transport goods.

Decorated Bases

Those responsible for making the molds for bottles used to ship materials usually chose to keep the sides unadorned, and to decorate the bases with identifying symbols or groups of letters. The figure of Mercury, the Roman god of commerce and money, was often chosen as a decorative emblem. Displayed here are both four- and six-sided bottles, as well as broken base fragments from similar vessels. There is great variety among the base designs, and consumers undoubtedly looked at these symbols to identify their preferred brands when making their selections in the market. Similar bottles used today have applied labels identifying the contents, but we have no evidence that such labels were employed in antiquity.

Mercury Flasks

Many square bottles are decorated on the underside with an image of Mercury, the Roman god of trade and commerce. This seems quite appropriate because such bottles were used to transport goods throughout the empire. The larger of the two square bottles displayed here has the same decoration on its underside as the base fragment placed in front of it. Within a series of letters that fill the corners is a draped figure seated on an armchair. The image is not detailed enough to identify the figure, and the letters surrounding the figure do not provide a clue as to the identity. The smaller bottle is decorated with an image of Mercury, also surrounded by letters.