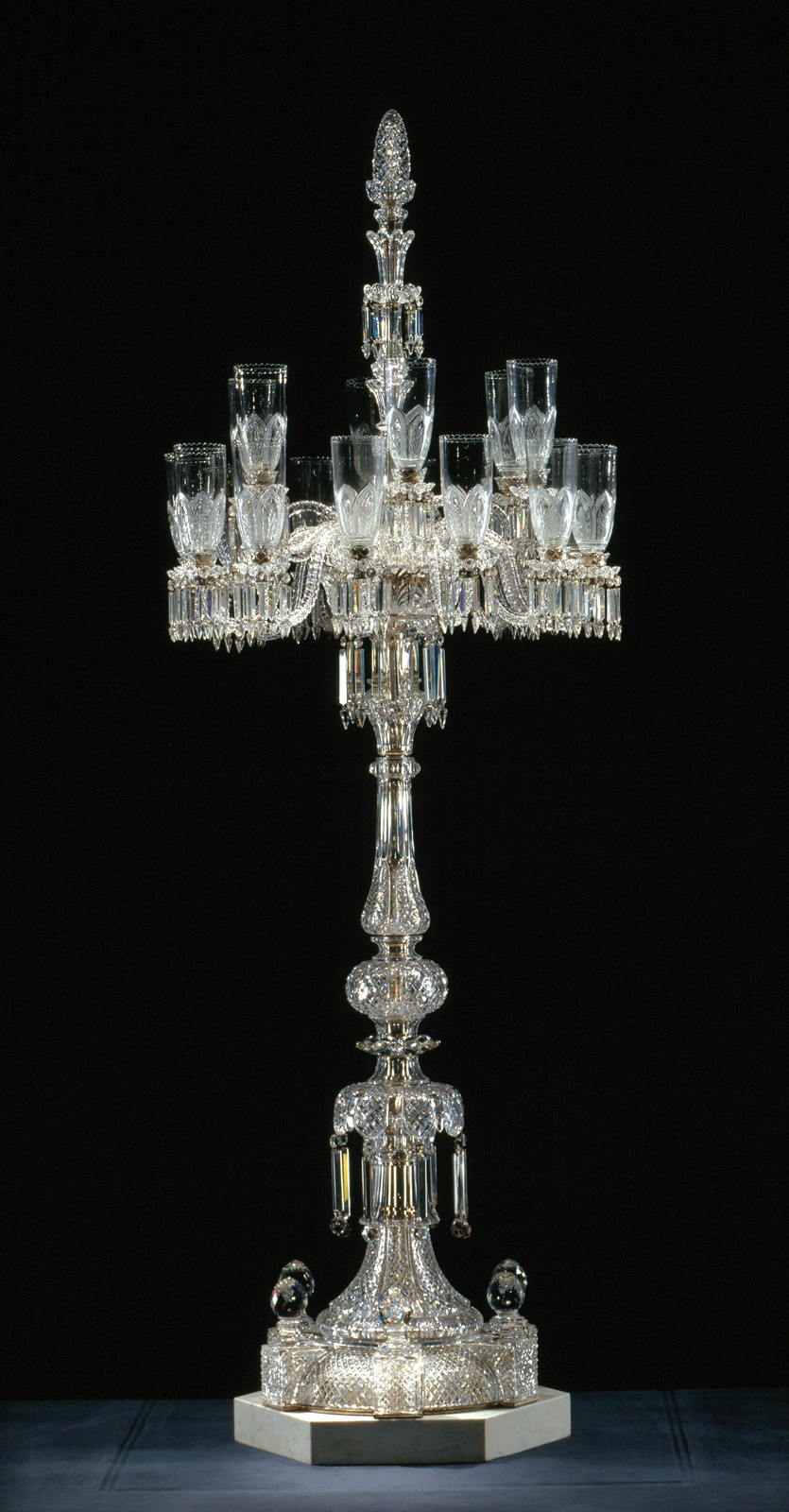

We recently had parts of a huge candelabrum in the lab. The piece was made by the English glass company, F. & C. Osler, around 1883, and stands almost 10 feet tall. Luckily the whole object did not need to come to the lab; only the tulip shaped shades were brought so that they could be washed.

Some of the shades are replacements for missing original ones. These replacement shades are made from a different glass than the originals, one that has an unstable composition. They are in the first or incipient stage of a degradation process known as “crizzling,” sometimes referred to as glass disease.

Two of the candelabrum's shade. The original on the left is clear, while the replacement on the right has become hazy because of incipient crizzling.

Crizzling is affected by two main factors, the composition of the glass and the climate in which it is kept, especially the relative humidity. During the crizzling process, moisture in the air leaches out the alkali elements of the glass which accumulate on the surface. The alkalis on the surface attract more moisture, sometimes to the point of forming droplets on the surface. This symptom of incipient crizzling is known as “weeping.” If the climate is drier, the alkalis can form as crystals. The alkalis also turn the surface hazy and slimy and have a distinct smell which I like to describe as dusty vinegar. A buildup of alkalis on the surface not only looks bad, it is also bad for the glass because it creates an alkali solution that starts breaking down the silica network of the glass. If the crizzling continues, the structure of the glass is eventually so compromised that the glass falls apart. The composition of the glass plays a huge role in how long it takes to reach the final stage of crizzling. Usually it takes many centuries, but if the composition is really unstable the glass can disintegrate in just a few years.

One of the shades being washed. The conservation lab has a plastic sink for washing glass to help prevent damage from accidental bumps.

Unfortunately, there is no way to reverse the crizzling process; the best we can do is slow it down. We do this by washing the glass to remove the alkali buildup and by making sure crizzling objects are kept in a stable environment. Air circulation around the objects also helps evaporate moisture on the glass surface.

The replacement shades on the Osler Candelabrum turn hazy about every 5 years which is when we bring them into the lab and wash the alkalis off the surface. The washing is done with tap water and a mild, conservation grade detergent, followed by thorough rinsing in de-ionized water to remove the minerals left by the tap water. The original shades were a little dirty, so we washed those as well.

More on crizzling: http://www.cmog.org/article/crizzling

View the Osler Candelabrum in the collections browser: http://www.cmog.org/artwork/candelabrum-0

2 comments » Write a comment