The other day, while looking for books on microscopes, I came across an old volume called Persio / tradotto in verso sciolto e dichiarato da Francesco Stelluti (Rakow bib. 95536). Imagine my surprise when I saw on the title page that the book was published in 1630 in Rome and dedicated to Cardinal Franscisco Barberini. This placed the book firmly in the world of Galileo Galilei. Because I love learning about the history of science and because I am a librarian (which, to me, entails being perpetually curious), this connection had to be investigated. Did this copy of Persio link me, however indirectly, to Galileo himself?

The answer turned out to be yes, on two levels. Persio was printed in Rome during Galileo’s lifetime (1564-1642). Galileo and Francisco Barberini were friends. In fact, Galileo was called to Rome and tried there in 1633 (Barberini defended him). So, there is a possibility, however extremely remote, that Galileo himself could have seen or even handled the Rakow Library’s copy of Persio.

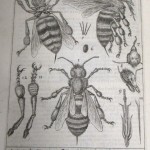

Second, Galileo was probably indirectly involved in the making of Persio. Persio (1630) is considered the first book to include microscopic illustrations. Persio is a work of verse (the Satires of Persius Flaccus) not science, but it includes a rather incongruous section about bees. Why bees? Bees were on the Barberini crest, and Francesco Stelluti, the author of Persio, was trying to court favor with the wealthy and powerful Cardinal Barberini.

The section on bees features a full-page illustration of them as observed through a microscope. This illustration was actually first published in short 1625 treatise, Apriarium, by Federico Cesi (Cesi was also trying to court favor with Barberini). The author of Persio, Stelluti, borrowed it for his book.

Illustration of three bees. Note the similarity to the Barberini crest. Image by the Rakow Research Library.

The image is also how Galileo is involved with Persio. Galileo, best known for his work with telescopes, also experimented with microscopes. He sent one to Cesi in 1624, and it was probably used to create the illustration.

Persio also features an illustration of a magnified weevil. As Cesi and Stelluti were both members of the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynx), Stelluti may have used the microscope Galileo sent Cesi to observe the weevil. Unlike the bee, the weevil does not appear to have any special significance, besides being mentioned in one of the verses.

Thinking of the game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, I believe coming across Persio and researching its history puts me three degrees from the great Galileo. Galileo probably lent the microscope that was used by Cesi and maybe Stelluti (degree 1) to make the illustrations in the Rakow’s book (degree 2), which I (degree 3) held and researched for this blog post.

Sometimes, the littlest moments remind me of why I love working in a library!

To learn more about the history of microscopes and Persio, you can read the Oklahoma University History of Science Collections blog; A. G. Keller’s article on Franscesco Stelluti from the Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, available through encyclopedia.com; and David Bardell’s article, “The Dawn of Microscopy,” from the journal, The American Biology Teacher.

1 comment » Write a comment